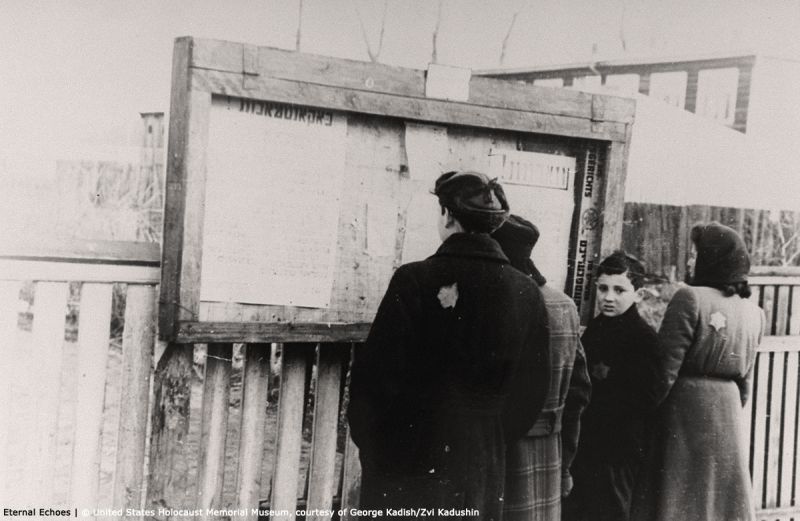

A small group of Jews reads the announcements posted by the Jewish Council in a display box on a street in the Kaunas ghetto.

I was there.

On March 27–28, 1944 about 1300 children (among them some 55 adults) were arrested in the ghetto and shot in the IX Fort. After the children action Tobias couldn‘t live in the ghetto legally. The mother contacted people in Kaunas to ask the help of her sister Maria Katinskiene.

Maria lived in Vilnius under Lithuanian identity. Tobias left the ghetto successfully. April – July, 1944 he lived with Katinskai family in Vilnius. July, 1944 Tobias’ mother tried to bribe the ghetto guard and leave the ghetto. She was shot. 1 August, 1944 the Soviet Army entered Kaunas.

Tobias Iafetas (1930-2019), Lithuania

Escape from the Ghetto

Tobias’ mother and her sister Maria who lived under Lithuanian identity organized Tobias’ escape from the ghetto. They wouldn’t succeed without the help of other people, priest Albinas, Konstantinas Jablonskis’ family and others. Tobias left the ghetto successfully and moved to live in Vilnius with his aunt Maria Katinskiene.

1) Listen to Tobias as he talks about his escape from the ghetto. Answer the questions.

1a. What actions did Tobias’s mother take to rescue her son?

1b. List the people and their actions who helped Tobias to survive during the war.

1c. What actions of rescue did depend on Tobias’s will? What actions of rescue Tobias couldn’t influence?

End of the War

April – July 1944 Tobias was hiding in the apartment of Katinskai in Vilnius. Tobias spent his time reading books and playing chess. He was lucky because no one identified him. July 11, 1944, the Soviet Army entered Vilnius.

2) Listen to Tobias as he talks about the end of the war. Answer the questions.

The German occupation ended in Lithuania because the Soviet Army entered the country. The Soviet occupation meant the start of arrests, deportation and murder of local people and suppression of the anti-Soviet resistance.

2a. How should we see and evaluate the military and political action of the Soviet Army, which meant life and partial freedom for Tobias and death to others?

2b. If you had to go into hiding and start living as if you did not exist, how would you occupy yourself? Would you have to overcome fear? If so, how would you achieve it?

Historical text

Holocaust bystanders, perpetrators and rescuers

The majority of Lithuanian people did not take a direct part in the Holocaust. They witnessed the Jewish tragedy, felt sorry for the victims and despised their perpetrators. But when the action was needed to help or save the condemned they did nothing. People remained passive bystanders. Fear of being punished for helping Jews led most Lithuanians to not get involved. Their survival instinct advised them to know nothing and ask nothing. Greed led them to steal the belongings of those who had been shot. Fear and compassion could not break the barrier of helplessness. The penalty for the help of the Jews was death.

Those Lithuanians who took an active part in crime came from different social classes, educational backgrounds and occupations. And motives for taking part in the holocaust were personal. Their motives for taking part in the crime were personal. Some placed their talents and efforts in the service of the Nazis while others took a direct part in the killings. As mayor of Joniskis town, Antanas Gedvilas stated, “When I started in that job I thought I would only have to do administrative tasks. Besides, I believed in the restoration of an independent Lithuania. But soon I became a perfect implementer of German orders.” In his war times diary, Zenonas Blynas wrote: “I cannot bear how /the Germans/ force us to shoot regularly, that Lithuanian do the shooting, that we become paid executioners, that they film us.”

There were people who later after the war were called the rescuers. Their support to the condemned varied. Some provided risk-free, accidental and short term aid that in effect did not alter a Jewish person’s eventual fate: they would comfort and encouraged people, warn of imminent danger, show the way to refugees, give them clothes and not disclose their whereabouts.

More risked those who provided serious, long-term aid. Assistance included saving Jewish property and handing it over to its owner in instalments (thereby saving a person from hunger and poverty in the ghetto), giving shelter to Jews for longer period, providing them with fake documents, hiding Jewish books, diaries, offering help during visits to the ghetto or relaying messages to other Jews. Some saved particular Jews; such as those individuals they had known before the war – neighbours, fellow workers and friends. Others provided help to whomever they saw in need, helping all they could. The rescuers, like perpetrators, differed with respect to their social status, education and wealth. Their motives for rescuing Jews also varied – opposition to German policy, sympathy, and sense of human duty, religious convictions, profit and self-interest. Many rescuers, like criminals, could not fully explain their motives.

Generally speaking, the lack of will to help and save others was present among Lithuanians. The same can be said about ghetto society. Most probably everyone would agree that self-concern and protection are characteristic to every human being, regardless of nationality. For instance, the Kaunas ghetto had to solve the problem of crime and heavy disagreements among individuals. For this purpose, the Judenrat established the ghetto court that carried out criminal and administrative cases (for example, the property share among the relatives and neighbours of the murdered person). The ghetto court functioned illegally because Gestapo was the only institution responsible for Jewish affairs. The existence of the ghetto court and the prison helped to keep the prisoners’ morale and diminished criminality. Alas, the court couldn’t help to solve the problem of the Judenrat representatives and employees who abused their position and status. Ghetto police and other officials misused their position and employed their family members and friends, took over property and goods from others and used physical force against other inmates. The Judenrat officials, even if they did everything correctly and legally, in the eyes of other inmates were seen as a privileged class.

It seemed in the ghetto where everyone was supposed to be equal since all were awaiting the same fate – death, different classes of people emerged. Some were more privileged than the others. Among the privileged, some consciously misused their position. Others did not give a thought about their actions. The third group were those who saved the weaker. In the end, everyone could easily change the category. All were just ordinary humans in the ghetto.

Author: Rūta Puišytė

Sources:

Žydų gyvenimas Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, 2007.

Raul Hilberg, Nusikaltėliai. Aukos. Stebėtojai, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas, 1999.

Documents Accuse, Vilnius: Gintaras, 1970.

3) Read the text about Holocaust bystanders, perpetrators and rescuers. Then answer the question.

3a. What were the choices of Lithuanian people regarding the Jews in WWII?

Choose Language

Choose Language  svenska

svenska  română

română  polski

polski  Lithuanian

Lithuanian  Deutsch

Deutsch  magyar

magyar