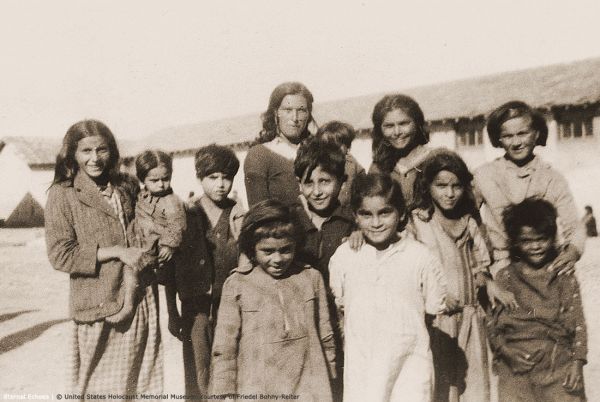

A photographer with a group of nomadic Roma. This photograph was probably taken in Czechoslovakia, 1939.

Introduction to the Romani Genocide

The persecution and murder of Europe’s Romani minorities (Roma, Sinti, and others labelled as "Gypsies") took place at roughly the same time and in many of the same places as the Nazi-led genocide of Jews in the Holocaust. In many cases, the same actors were responsible for the violence, such as German SS killing squads, members of the police, and local collaborators. Despite these similarities, however, the Romani genocide should be considered a separate historical event with its own causes and particular results in different countries. Its legacy in these societies is also very different from that of the Holocaust.

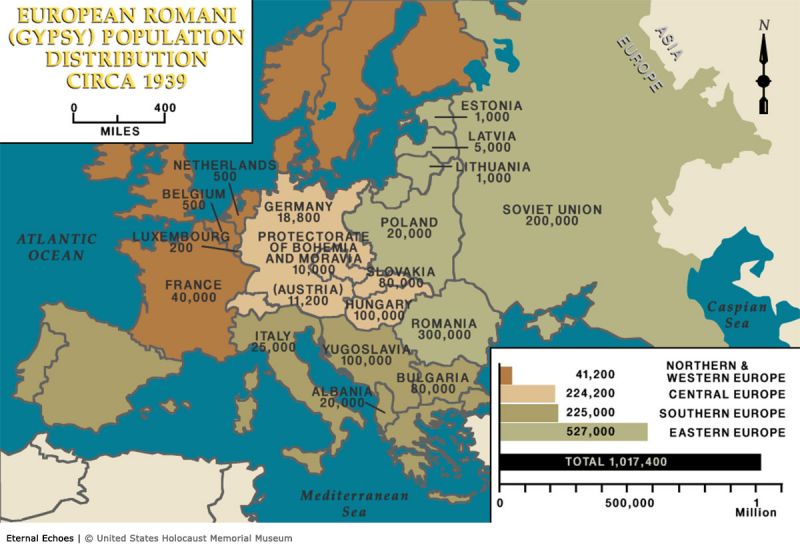

Europe's Romani Minorities

The Romani people are known by many names; they may call themselves Roma, Sinti, Manouches, Cale, Romanichals, Travellers, or a variety of other words in their own language. Many majority societies, however, simply call all these groups "Gypsies", a word that usually has negative associations. The fear, mistrust, or hatred of Romanis and other groups in society considered "Gypsy-like", is nowadays called antiziganism (also anti-Gypsyism or anti-Romaism).

The ancestors of the Romanis and related ethnic groups – the Domari ("Nawar") in the Middle East, the Lomari in Armenia, the Lyuli of Central Asia – left their original homeland in India in waves of migration beginning around 500 CE.

By around 1000 CE, the ancestors of today’s Romanis arrived in the Byzantine Empire. Over the next few centuries, they adapted to elements of Byzantine Greek culture and became Romanis – a part of the family of European peoples.

The different Romani groups continued to develop, both due to their migration routes, and through interacting with the societies where they ended up staying. This led to the current wide variety of spoken dialects, traditions, occupations, and religious beliefs among the Romani groups around Europe today. For example, Finnish Roma speak a dialect of Romani that has been influenced by the Finnish language, and their traditional dress differs greatly from that of Spanish Cale or Hungarian Roma. Yet all Romani groups today retain elements of an original, common Romani culture, even though the combinations of elements might differ from group to group.

Antiziganism and Persecution of "Gypsies" before the Nazis

Similar to antisemitism, the history of antiziganism is almost as long as the history of the Romanis in Europe. Antiziganism is to be found in all European – and many non-European – societies. It is the basis for what became a genocide against the Romanis in Europe during World War II.

By the 1600s, a number of stereotypes about “Gypsies” had already become widely spread throughout Europe. Such stereotypes could be that "Gypsies" are by nature criminal, dirty, unreliable, deceitful, immoral, and uninterested in honest work and a normal way of life. Instead, it was felt that "Gypsies" preferred to move from place to place, begging, stealing, entertaining, or doing simple temporary labour to make a living. Unlike the permanently settled population, "Gypsies" were viewed with suspicion as, at best, dangerous foreigners, and at worst, evil representatives of the Devil.

The resulting mutual sense of mistrust and wariness led to a situation where "Gypsies" were kept on the margins of society, and the Romanis adapted their ways of living to cope with this exclusion by majority populations.

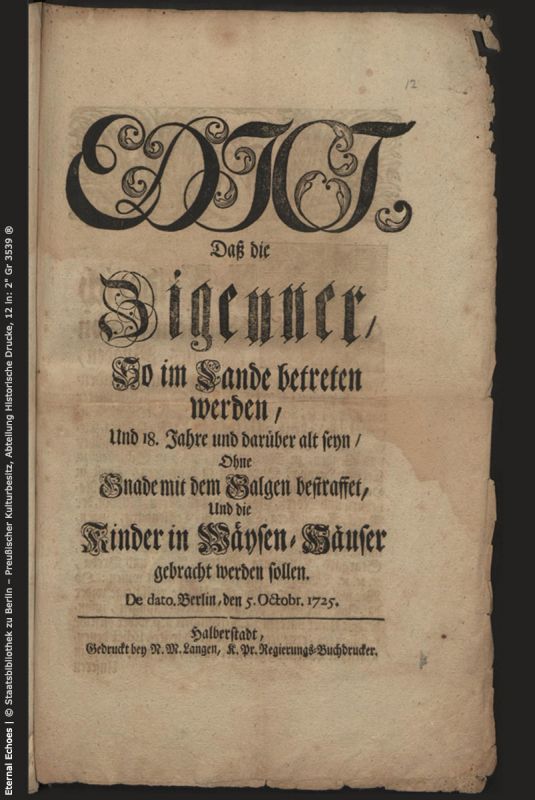

Already in the 1600s and 1700s, Romanis were targeted by antiziganistic laws and regulations in many European countries. Because Romanis were often accused of criminality, witchcraft, spreading disease, or spying for the enemy, "Gypsies" were prevented from remaining in any one place for too long, and excluded from various activities, such as owning property or taking part in Church ceremonies.

In Spain and Hungary, the government forcibly resettled Romanis and forbade their language and culture, in an attempt to make them into “honest” peasants. In Scandinavia, laws allowed for male "Gypsies" to be killed on the spot and women and children to be forced to leave the country. In Romanian lands from the late Middle Ages up until the 1850s, "Gypsies" were owned as slaves by powerful landowners, including the Church. These examples show that, across Europe, to be labelled a "Gypsy" meant being considered a problem or a threat, and therefore deserving fewer rights than a regular person.

In the 1800s, the rise of the modern nation state created new forms of antiziganism. New ideas promoting "pure" nations and "races" said that "Gypsies" are inferior and do not belong. The development of a modern, capitalist market economy also led to the belief that the "Gypsy" way of life was backward, unproductive, and therefore should be forbidden.

As these attitudes also began to influence politics, the police – a key institution of all modern states – came to consider fighting "Gypsies" a priority. Step by step, being a Romani came to be equated with being a criminal, and because of nineteenth-century ideas about how criminal traits were passed on though families, "Gypsies" were seen as criminal from birth. Therefore, already before World War I, in Germany, France and some other European countries, the police had powers to register and keep close track of all "Gypsies" in their territory.

Many policemen saw it as their job to prevent the spread of the "Gypsy Plague", as it was often called in the public debate.

Nazi Treatment of the Sinti and Roma, 1933–1939

The rise of Hitler’s Nazi party to power led to changes that affected Germany’s two main Romani groups, Sinti and Roma. These changes, while similar to the processes of exclusion and persecution that targeted Germany’s Jewish inhabitants, can be considered a separate, parallel development driven by slightly different interest groups within the Nazi system.

In contrast to his prominent antisemitism, Hitler rarely talked about "Gypsies". The pressure to do something about the alleged "Gypsy Plague" came from within the German police, particularly the Order Police (by contrast, anti-Jewish measures were often carried out by the German Security Police). As the Nazis reorganised Germany’s police forces into a unified structure under the control of the SS, those who demanded something be done about the "Gypsies" gained strength in numbers.

From 1933, existing laws against "Gypsies, vagabonds, and workshy", as well as the new Nazi law on "habitual criminals" led to widespread arrests and police harassment of Romanis. From 1936, a central police office for "combatting the Gypsy nuisance" was created in Munich, where the Bavarian Police had been keeping registers of the "Gypsies" since 1899. Following various local actions, like the forced clear-out of Romanis in conjunction with the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a country-wide "Gypsy clean-up week" took place in June 1938, the same year as the November Pogrom against Germany’s Jews. In December 1938, Heinrich Himmler, as head of the SS and German police, sent out an official policy document to all police on "combatting the Gypsy nuisance".

The attitudes about the "Gypsy Plague" also affected other policies directed against the Romanis. Interior Ministry experts, reflecting the views of the police, argued that the discriminatory racist regulations of the so-called Nuremburg Laws of 1935 should also consider "Gypsies", alongside Jews, as being racially foreign to Europe and therefore not to be considered equal to ethnic Germans. The 1933 law on forced sterilisation, to prevent "inferior" people from having children, was used against people of Romani background.

A police psychologist named Robert Ritter was tasked with registering and racially profiling all the "Gypsies" in Germany and Austria, first for the "Racial Hygiene Research Office" of the Ministry of Health, and later for the "Institute of Criminal Biology" for Himmler’s Security Police. Ritter and his assistant, nurse Eva Justin, collected a large database of sensitive information about thousands of Sinti and Roma, and helped advise the Germany authorities on policy matters concerning the "Gypsies".

In Nazi Germany, those considered "Gypsies" could be arrested and sent to concentration camps, thrown out of service in the armed forces, and stripped of their citizenship. With the outbreak of World War II, the persecution changed into genocide, which spread to those countries that came under Nazi Germany’s control or influence.

A European Genocide, 1939–1945

At the time, antiziganism and policies directed against "Gypsies" were not unique to Germany. During the 1920s and 1930s, international police cooperation within the new organisation, Interpol, based in Vienna, discussed the perceived problems of "Gypsy criminality" as a national and cross-border problem a number of times, even more so after Nazi Germany took control of Interpol following the annexation of Austria in 1938.

Through the meetings of Interpol, police from across Europe compared their local attitudes and saw that there was a common view of the "Gypsies" as a serious threat to law and order that needed to be closely watched and swiftly punished. As evidence of this belief, when France declared war on Germany following the invasion of Poland in 1939, one of the first actions of the French authorities was to intern in camps all "Gypsies" in areas near the German border, as it was suspected that they could act as spies for the Germans, recalling a centuries-old antiziganstic stereotype.

In some places, local conditions led to unusual decisions: for example, in Lodz in 1940, "Gypsies" were forced into the Jewish Ghetto. In late 1941, the German naval commander ordered all the "Gypsies" removed from the coastal city of Liepāja and shot, because he considered them a security threat. The only survivor was a single Romani woman who was forcibly sterilised instead, a case that was eventually mentioned as evidence at the post-war Nuremburg war crimes trials. The action in Liepāja, while overseen by the German police, could only be so quick and thorough thanks to the fact that the local Latvian police already had detailed lists of the city’s entire Romani population, right down to infants.

In German-controlled Eastern Europe, the main wave of mass shooting of Romanis came in 1942, after most of the local Jewish population had already been murdered by the Einsatzgruppen and Security Police. Here, the local police forces had much greater room for deciding how to interpret and implement instructions coming the German authorities. The chain of command was weaker between the German Order Police that promoted "anti-Gypsy" measures and the local police chiefs, as compared to how carefully the German Security Police oversaw anti-Jewish actions.

At the same time, some local police chiefs also saw the wartime situation as an opportunity to be rid of the "Gypsy nuisance" once and for all. Therefore many of the decisions about which Romanis were to be arrested, which to be killed, which to be sent off the concentration camps, and which to be left alone, was very much a choice of the local police chief, rather than some German official higher up.

As a result, the fate of Romanis could vary drastically from police district to police district even in the same country, depending on the prejudices of the local chief of police, prefect, or mayor. In some instances, local mayors, police, or clergy used their authority to prevent the murder and persecution of local Romanis.

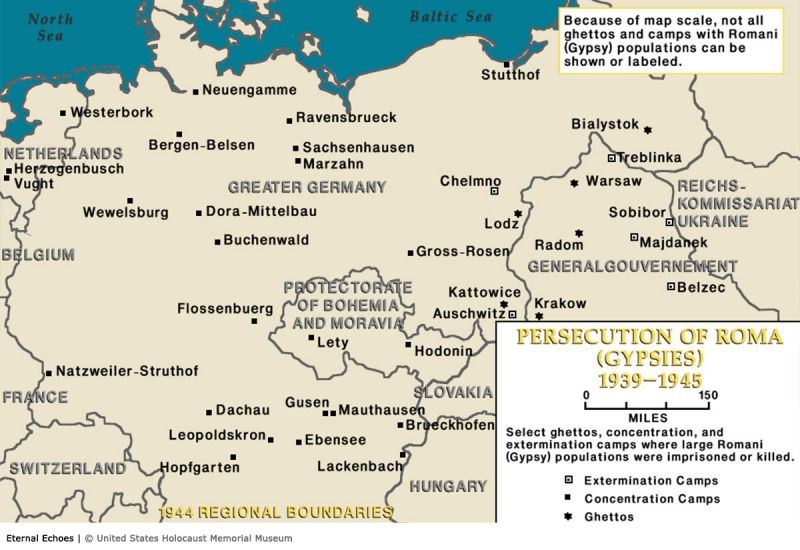

Throughout Europe from 1942 to 1944, local police forces increasingly arrested "Gypsies" and sent them to prisons or labour camps. Already in 1942, large numbers of Polish Roma were sent to be gassed to death at Treblinka. That same year, Himmler ordered the deportation of "Gypsies" to the growing camp complex at Auschwitz.

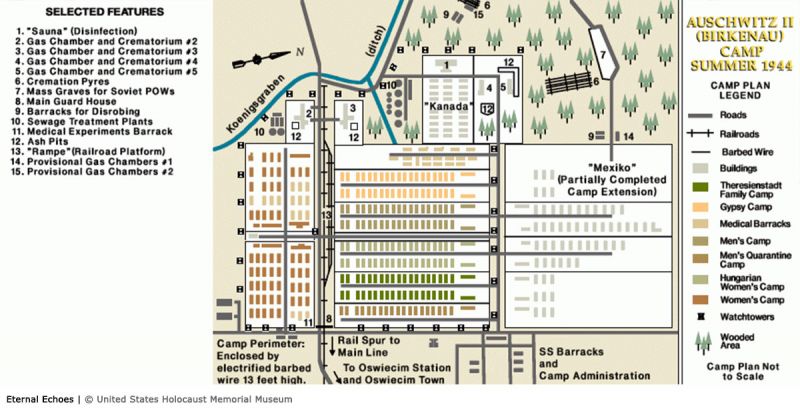

In February 1943, Himmler ordered that "Gypsies" from all over Europe be sent there, and a special section of Auschwitz-Birkenau, known as the "Gypsy Camp" was created to hold family groups – in most concentrations camps, the men were always separated from women and children.

On the night of 2–3 August 1944, the SS guards closed down the "Gypsy Camp" at Auschwitz, gassing the majority of the inmates and sending the rest to other concentration camps as slave labour. This date is now marked by many Romanis to commemorate the victims of the genocide.

Non-German fascists and authoritarian allies also took part in planning and carrying out the genocide against Europe’s Romani minorities. The Croatian Ustaša regime murdered Roma in large numbers, often not bothering to keep records of how many. When the Hungarian Arrow Cross fascists took control in a 1944 coup, they also unleashed a wave of murder against Roma there.

Romania’s leader Ion Antonescu, who was allied with Hitler, ordered Romanian Roma to be forcibly marched to Transnistiria, territory Romania had newly conquered from the USSR, where thousands of Roma perished of starvation and disease because they had nowhere to live and no way to make a living. At the very end of the war in 1945, Vidkun Quisling was still planning how to “solve the problem” of Romanis in Norway, as it was no longer possible to send them to Auschwitz.

Even Finland, which had invaded the USSR along with Nazi Germany, had been pressured to impose anti-Roma policies, until the Soviet Union forced Finland to change sides in 1944 and fight the Germans instead.

Romani networks of family and friends also could go to great lengths to hide and rescue those being hunted by the German or local police, sometimes even non-Romanis, like the Latvian Jew Valentīna Freimane, who described the help she received from a Roma woman in her memoirs.

Liberation and Legacy

In 1945, surviving Romani inmates were freed from the Nazi camps, and many tried to return home. They were often not welcomed back, though, but instead met with continued prejudice based on long-standing antiziganism.

Even after the defeat of Nazism, the common perception that "Gypsies" were a potentially criminal social problem group remained strong. In the few cases in post-war West Germany where policemen were tried for their role in the murder of Romanis, they were able to successfully argue that they had been acting in a crime-fighting capacity, and not taking part in genocidal Nazi crimes against humanity. Reflecting a view that "Gypsies" are criminal by nature, the courts accepted this argumentation and freed the accused on these charges. Eva Justin was also able to avoid legal responsibility for her role as Ritter’s assistant, and could even continue research on Germany’s "Gypsies".

As late as 2000, the influential scholar Gunter Lewy could argue that the Romanis were not victims of a genocide, because the Nazis and their allies persecuted and killed "Gypsies" as alleged criminals, spies, and bearers of disease, and not because of they were Romanis.

Even in the communist countries of eastern Europe, where racism was said to not exist, popular antiziganism existed below the surface. The official view of communist governments could acknowledge individual Romanis as victims Nazi or local fascist crimes, but as with the Jews, the Romani tragedy was simply included in the overall suffering of the people during the war, not recognised as a specific genocide. Furthermore, communist governments also viewed the "Gypsies" as a problem for society, but one that would be fixed by social policies that would turn them into good, productive workers.

Choose Language

Choose Language  svenska

svenska  română

română  polski

polski  Lithuanian

Lithuanian  Deutsch

Deutsch  magyar

magyar